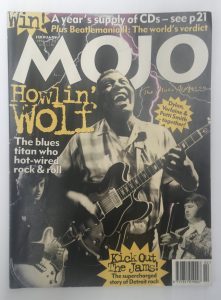

Chester Burnett, the otherworldy musician known as Howlin’ Wolf, was born 113 years ago this weekend. Right at the time I was finishing Portrait of the Blues, and an early version of my Iggy bio, I was fortunate to receive a phone call from Mat Snow, editor of MOJO, asking for a long, detailed story on the man.

I’d already tracked down Hubert Sumlin in Milwaukee – an incredible day – Pops Staples who’d seen Wolf at the Dockery, plus many other musicians who’d worked with Wolf, and this gave me the impetus to find the last few of his colleagues alive. This was, I think, the last major piece on Wolf to run that featured most of his musicians, and was extracted by Peter Guralnick for his book that accompanied Martin Scorsese’s series, The Blues.

Now, nearly 30 years on, most of those wonderful characters are gone. I miss them.

This is the first draft of my MOJO story, which might well have errors corrected by MOJO’s expert team, especially features editor Jim Irvin, but it restores my encounter with Willie Johnson, one of the Wolf’s key lieutenants and one of the most difficult too.

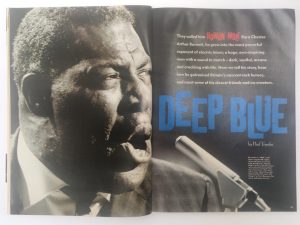

Deep Blue: Part 1

Hubert Sumlin shuffles through a pile of mementoes, letters, photographs, and cuttings before one of them catches his eye. ‘Hey, this is from when they put Wolf on a stamp – the mayor of our city got me down for a ceremony, to honour me! Can you believe it? Things change, man. I never thought it would happen in a million years, but, hey, I am glad it did.’

The wood-panelled basement of Sumlin’s neat little house in Milwaukee is crammed with memorabilia from the man’s 20-year long history playing Keith Richards to Howlin’ Wolf’s Mick Jagger. Hundreds of photos fill the walls, showing Hubert being feted by politicians, or being hugged by Stevie Ray Vaughan or Robert Plant (‘Don’t know who that guy is, but he was real friendly, gave me that picture himself!”). Stacks of CDs line the shelves: Charley Patton or Robert Johnson records that Sumlin first heard back in the Thirties when he was playing an improvised one-string guitar nailed up on the side of his house, or Wolf Box sets which unearth long-forgotten sessions from the Fifties. ‘I couldn’t believe they had this material left, man!’ he chuckles. ‘I was the first somebody to hit the store, all this stuff by people I heard when I was a little bitty kid, and all these records I done forgot, man!’ But, hey, I am glad. These people, they paid their dues and this is something that is going to help the youth, the young generation to think, hey man, people you didn’t thought would make it, taught you things. When you gone people think about you, I think that’s great. It shows if you mean what you say and you mean what you do, everything is alright. Tell the truth. I think they proved themselves to the people, these here Blues and everything, and if you want to be a hero, you can be what you want to be. This is it.’

*****

Twenty years after his death, Howlin’ Wolf’s Fifties recordings are still being used by the world’s advertising industry as a totem of authenticity, used to sell jeans or beer. But repetition has not tamed the Wolf’s howl. Wolf’s music came from the very wellspring of American music, sourced directly from the plantation in the Mississippi Delta where scholars believe the Blues originated. Yet Howlin’ Wolf, the rustic, surly supposed simpleton was also an iconoclast, one of the first musicians to unleash electric guitars on an unsuspecting world, and therefore an appropriate starting-off point for Jimi Hendrix, who signalled that he was picking up where Wolf had left off by opening his milestone 1967 Monterey set with Wolf’s Killing Floor. Wolf and Hendrix both met with similar misconceptions. In the Sixties there were English musicians, like Eric Clapton who put Hendrix’s appeal down to a kind of innate ‘spade’[sic] genius, rather than recognising that he was simply technologically way ahead of them, with a greater command of guitar and recording techniques. Back in the Fifties, Howlin’ Wolf had met with similarly patronising assessments. Described by Sam Phillips as ‘a force of nature’, Wolf was in reality far more complex. He learned his trade from the most far-out musicians of the Thirties, such as Robert Johnson, and went on to run his own group as a ruthlessly efficient organisation, heading one of the first fully electric outfits in the Mississippi Delta. His Chess records, masterfully realised symphonies that combine proto-metal riffs with off-the-wall bebop rhythms, were used as blueprints by everyone from Led Zeppelin to The Rolling Stones, Captain Beefheart to Tom Waits. But there are good grounds for contending that these white interlopers, rather than developing Wolf’s themes, merely watered them down to a more palatable form. Ten years before Bob Dylan first opened up the imagery of Rock lyrics, Wolf and de facto producer Willie Dixon were using surreal, bizarre allusions and dark metaphors that came from both black folk-lore and the unfathomable recesses of his own psyche. When John Lennon was asking to hold his baby’s hand, Wolf was complaining that he’d asked for water, and his woman gave him gasoline. When Mick Jagger was asking his girlfriend to tell him she was coming back, Wolf was howling how he’d been left on the killing floor – the bloody slaughter zone familiar to practically every inhabitant of South Side Chicago, who’d either worked in the huge local abattoirs or could hear the animals squealing above the bustle of South 64th St.

No shambling cottonpicker, Wolf was hip, as he had to be in the ruthlessly cut-throat arena of Forties and Fifties American black music. Wolf and his band didn’t go electric because of some namby-pamby theories about tonality and reflecting the urban angst, man. They went electric so they could blow their horn-oriented Jump Blues rivals off stage. They were the baddest motherfuckers around, and they made cutting edge pop music, like Hendrix did in the Sixties, Prince in the Eighties, or Tricky in the Nineties.

****

Down in Mississippi, on Highway Eight between Cleveland and Ruleville, lies the Dockery Plantation, where Henry Sloan and Charley Patton held court 70 or 80 years ago. Sloan and Patton were both playing what we’d now call Blues at the very beginning of this century, and if the origins of this complex music can be traced to any one location, then this flat, seemingly barren and god-forsaken area is it. Just a couple of miles away, Highway 61 cuts across the old route of Highway Eight. This is the cross-roads where, according to Mississippi legend, Bluesmen such as RObert Johnson cut their deal with a black man who would retune their guitars, giving them supernatural musical powers in exchange for their immortal soul. A romantic legend, maybe, but the Devil walks close in this area of Mississippi, an oppressive third-world location where travelling musicians were in ever-present danger of being jailed as vagrants, and where the Ku Klux Klan still meets regularly today. In the early years of this Century Will Dockery’s farm was one of the area’s more enlightened plantations, where black people could work or play with minimal interference, and the Dockery became a regular centre for social gatherings, as well as a stopover for passing musicians.

Chester Burnett’s family moved from Clay County to Ruleville in the early Twenties. Wolf used to tell various stories about how he’d won his name; his favourite version was the one where he described how his daddy had killed a wolf and brought it home to show his son. Young Chester was terrified by the fearsome carcass and learned to imitate its howl, so that he could scare off any of its companions that might be out to get him. Soon after his arrival in Ruleville the young Wolf started to hang around with Patton, who was just as much showman as Blues singer, playing his guitar behind his head or even, for the right audience, simulating copulation with his guitar, starting a tradition which would be taken up by Guitar Slim, Johnny Guitar Watson and Jimi Hendrix. Burnett absorbed both Patton’s stagecraft and his guitar playing. Roebuck ‘Pops’ Staples, the man who provided the soundtrack to the Sixties Civil Rights movement with his family group, The Staple Singers, was one of many Dockery workers who saw Wolf and Patton play the local fish fries and picnics.

These days Staples is a tall, magisterial-looking 80-year old, who with his white Kaftan, specs and air of authority could pass for an African Head Of State. Brought up on the upper Dockery plantation, the young Roebuck Staples was a skilled horseman, respected in the neighbourhood, and looked over by a hard-working father who ensured his son never came into contact with the white man: ‘My daddy was one person they didn’t pick on. He knew how to farm and he knew how to work, and he didn’t allow the white man to ride over him. My grandfather was a slave, but my father never would live on a plantation that would have people telling him what to do. So we didn’t have that problem.

‘Only thing was, my daddy thought the Blues was the Devil’s music. Wouldn’t even let me play the guitar, said that was the instrument of the devil, too. So I’d sneak out of the house, and that’s how I saw Charley Patton and Wolf, when I was 12 or 13. It would be where someone had a big house, and on Saturday night they’d organise a dance. Ladies would be cooking chicken and chitlin’ in the kitchen, and they’d have a room for gambling, playing cards, drinking bootleg liquor, and a big room out in front where they’d play and dance. Charley and me was on the same plantation, he’d always be playing there, and Wolf came along later. Wolf was my main man. Charley Patton was a good man far as I know, I was young and didn’t know about his life or anything. But Wolf, I thought he was the greatest thing. A big guy, a real tall handsome man, he was really something else. He was just a few years older than me, but he was so powerful I wouldn’t even dare to speak to him. They were already calling him Wolf then. He was playing with Charley, I think he was maybe playing Charley’s songs, but he was something different altogether. As far as I was concerned, he was the Blues.’

Whatever Wolf’s promise in those early years, in his own eyes he threw it away. According to Hubert Sumlin, ‘his time was too short, man, on earth. He told me he was 40 years too late, I didn’t know what he meant at first. One night we was riding from Chicago in the bus with all the band, everybody sleeping but me and him and he come to telling me what he meant. He say, his mother put him out on account he wouldn’t work and his uncle raised him. He was almost 40 years old, I believe, before Sonny Boy met his sister and he realised what he wanted to do. He said he started at 40, and that was 40 years too late.’ From the mid Twenties to the mid Thirties, Wolf worked outside of music, and was only dragged away from farming by Little Boy Blue – Alex Rice Miller, a conniving, irascible, card-shark operator of the first degree, who would later ‘borrow’ the persona of the famed harmonica player John Lee ‘Sonny Boy’ Williams.

Rice Miller liked to ramble. He’d hit the road playing harmonica with the now-legendary Robert Johnson, as well as with Johnson’s protégé, Robert Lockwood, and was fast becoming a well-known figure in the incestuous music scene of the upper Delta. Williamson played up and down Mississippi from Gulfport in the South, up to Brownsville, Tennessee, 400 miles up North. Williamson never seemed to keep his accompanists for too long, and after he’d taken up with Burnett’s half-sister Mary persuaded him to accompany him on guitar for some dates around Arkansas and Mississippi. Later on, Burnett accompanied both Johnson and Lockwood, two of the most consummate guitarists in the Delta, who were both capable of throwing a polka or hillbilly number into their set, but could also deliver some of the darkest, most-fully realised and intense Blues that had ever been made. But where Johnson and Lockwood were happy to ramble from town to town, evading irate plantation owners and the law, Burnett’s religious, farm-based upbringing kept calling him back to the land. In and out of music over the next few years, the Wolf wouldn’t commit himself fully to music until he returned from military service in 1946, and immersed himself in the crazy bustle of Memphis, then the site of some of the most momentous developments in the history of popular music.

*****

Memphis, Tennessee 1948. A huge strangled hoarse warm rich throaty voice crackles out of thousands of Crosley and Emerson radios from Helena Arkansas to Holly Springs Mississippi: ‘This is the Wolf comin’ at ya from KWEM in West Memphis, your only real home for the real down-home Blues. Now Howlin’ Wolf and the House Rockers is gonna play you an old-time Charley Patton number, but we kinda jazzed it up a little, and I think you cats are gonna like it.’ Suddenly a vicious riff cuts through the ether, as Willie Johnson slams out the chords on a beat-up Sears acoustic which he’s electrified with a De Armond pickup. His little Silvertone amp is cranked up so loud that it buzzes with distortion, vibrating so hard it starts dancing across the studio floor. The radio engineer pulls down the master fader and shakes his head in despair. What is it with these guys, and why do they have to play so goddamn loud? Jeez, you can probably hear them across the Mississippi without the aid of a radio!

Willie Steel takes up the shuffling drum beat, while the pianist, an outwardly placid man who nevertheless goes by the name ‘Destruction’, pounds violently on the long-suffering upright honky tonk in an effort to make himself heard over Johnson’s barrage. Then Chester Burnett, aka Bigfoot, aka Bull Cow, aka the mighty Howlin’ Wolf, stomps up to the solitary Decca valve microphone in the middle of the studio and starts to howl, instantly drowning out the mayhem behind him. Again, the engineer shakes his head. He’s checked the mike and checked the mike, but he’s damned if he can work out why every time the Wolf opens his mouth it sounds as if it’s blown a valve! As the little guy, James Cotton, takes over the mike for a harp solo it sounds perfect, then when Wolf starts singing again it suddenly sounds all rasping and distorted. He makes a mental note to check the mike after the show, then sits back and listens to the music. The band aren’t bad, really, and the big guy really knows how to sell airtime – he’s brought in car dealers, seed suppliers and bread wholesalers since he started his own programme – plus he’s pulling nearly as many listeners as Sonny Boy, who brought him to the station. When he’d been introduced to Wolf and saw his band were using those new-fangled electric guitars, he thought they were just another bunch of Sonny Boy imitators. Then he’d heard them play. Even if it is just race music, this is nearly as good as Hank Williams!

‘Don’t want to marry ya baby – I said, I just wanna be your man…’ Wolf roars, as his fame begins to percolate through the upper Mississippi Delta. Before long his music will reach the ears of everyone from Little Milton to BB King, Otis Rush to a young white boy named Elvis Aaron Presley.

*****

‘It was the radio started everything off round here,’ rasps James Cotton in his trademark throaty Mississippi drawl. ‘Sonny Boy was the first one, then I ended up in Wolf’s band on KWEM when I was 12 or 13. We did 15 minutes a day sponsored by House Of Bread. I had my own show too, later on. Poole’s Discount Motors in Memphis bought the time, it was a favour to you to get people to hear your music, and we helped sell them lots of cars, too.’

Cotton has seen his fair share of cities playing the Blues. He moved from Tunica Mississippi to Helena Arkansas to play harmonica with Sonny Boy Williamson’s groundbreaking electric band in the early Forties, then later spent 10 years playing in Muddy Waters’ legendary Chicago band, before moving to San Francisco with Paul Butterfield in the summer of love. But now he’s back in his spiritual home – a bar on Beale Street, Memphis. Despite the fact it’s now a commercial shell overrun by white tourists, this is the street that was the centre of Southern black culture back in the Forties. This is the city where electric Blues was created in 1939, when Robert Lockwood fitted a Montgomery Ward pickup to his guitar and started using it on his dates with Sonny Boy Williamson, effectively establishing the rock ‘n’ roll format of electric guitar, vocals and drums, before spreading the new sound across the South on the King Biscuit Time radio show. This is the city where Blues was beaming out from stations like WDIA and KWEM from the Forties, planting the seeds that would germinate into white Rock ‘n’ Roll. This is the city where what we know as Chicago electric Blues really originated.

‘When I got to Memphis in the Forties, they still had jug bands in Handy Park,’ croaks Cotton, settling back and ordering a couple more Budweisers. ‘If you wanted to amount to anything, this is where you came. Everybody was here: Wolf, BB, Walter Horton, Roscoe Gordon, Ike Turner, and other guys you don’t hear nothin’ about now, like Willie Love. It was Sonny Boy introduced me to Wolf. Wolf was really a quiet kind of guy who liked people to leave him alone, but if they gave him trouble he’d give ’em trouble back. Sometimes you had to be mean back then the way everything was.

‘This was a great place to play, except when the clubs would try and get away without paying you. Down here was the main drag, you had cafés selling soul food, guys shining shoes, guys telling jokes, guys going up and down the street tap dancing. We had the Handy Theatre then, and a hotel called The Sunbeam where we’d have Blue Mondays and play all day and all night. This was the kinda city that was filled with people who don’t work, and they just got money anyway, you know what I mean? It was happening and it was all black, and I’m not being racist when I say that, I’m just telling it like it was.’

‘Soon as I got with Wolf he was electric, way before everybody ‘cept Sonny Boy and his band. See, round here there’s so many musicians that it’s real competitive and you’re up against these big bands with the saxophones. Now Wolf would never let anybody out-do him on stage, that’s where the tail dragging and everything came from, and the band was the same. No-one was gonna cut us. ‘Scuse my language, and I know you’re gonna block this out, but with the amplifiers and everything we go could go up against a nine piece band and blow the motherfuckers right off the stage. We annihilated them, man.

‘It was Ike Turner got us recording, he played piano and was acting as some kind of talent scout for the Sun label, they was paying him to find people to record, so we went in there and recorded Howlin’ At Midnight and How Many More Years. It was a little old room, we just played how we felt and Sam Phillips kept himself busy getting the microphones right. We didn’t think we were making a new sound or anything, we were just playing the way we played. Sam Phillips got real excited, he was real friendly and ‘far as I was concerned he was a real nice person. Then times changed and I don’t know where things went from there, ’cause I did four songs for him and never got any money. That was way before you ever heard of Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins or Jerry Lee Lewis. Then Wolf decided he was gonna go up to Chicago, so he left Willie behind and took Hubert along with him. So that was the last I saw of them ’till I got to Chicago.’

Sam Phillips had sent tapes from Wolf’s first sessions both to Chess in Chicago and Modern in California, causing a contractual dispute which dragged on until February 1952. Over the intervening months Wolf would cut with Sam Phillips in Memphis for Chess, and with Ike Turner in West Memphis for Modern, but it was the Chess version of Moanin’ At Midnight that became a hit, catapulting Wolf into the vanguard of a new movement. Wolf, Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker represented a radical realignment of the Blues, combining a back-to-basics traditional Delta Blues approach with electric instrumentation and a powerful dance-orientated beat. ‘It was a complete change,’ says Billy Boy Arnold, who at the time was playing on the Chicago streets with Bo Diddley. ‘In 1948 the major artists on the scene were people like Memphis Minnie, Big Bill Broonzy and John Lee Williamson. But by 1952 the scene had changed drastically, and I mean drastically. Muddy and John Lee were the first, then Wolf came on the scene, and the electric sound had taken over. From then on you had BB King, Guitar Slim, Elmore James, all of them electric, and Big Bill Broonzy and those guys who had been on the scene for 30 years just faded out.

Wolf’s records were state of art, and instantly put him on a competitive level with Muddy Waters, who had only just started using a full electric band on record. If anything Wolf’s records were more aggressive, combining Wolf’s monstrous voice with a radical new aggression and vibrancy epitomised by Willie Johnson’s searing over-amplified electric guitar. By the end of 1952, Wolf was ready to make the move to Chicago, where he could record in Chess’s own studios, and where there was seemingly limitless work in the South and West Side clubs. But Johnson, a major architect of Wolf’s sound, would remain in West Memphis. ‘It wasn’t no surprise,’ says Cotton, ‘Willie and Wolf would just argue all the time like cat and dog, and Willie could be pretty mean, too. It just got to be too much trouble for the old man.’

Johnson remained active in the Memphis scene after the departure of his employer, and moved to Chicago in 1956 when his replacement, Hubert Sumlin, temporarily defected to the rival Muddy Waters camp. After Wolf had thrown him out of the band for good, Johnson played occasionally in the city with some Arkansas contemporaries such as Sunnyland Slim, but by the Nineties he was rarely seen in public. Tracking Johnson down to find out why he’d faded away from the scene would prove a tricky exercise, despite the efforts of Michael Frank, a Chicago label owner who was planning to make a record with Willie and Sunnyland Slim. Johnson lived down on 56th and Indiana in the South Side, in a typical Chicago Victorian building with a bunch of kids sitting on the stairs up to the entrance, and a gloomy nicotine-coloured hallway where, if you’re waiting for Willie, you get to spend lots of time. Three prearranged dates passed before Willie finally showed up as promised. Sitting on his bed in an otherwise bare room, thin and wiry with a shock of Rodney King-style electrified grey hair, Johnson looked on without a glimmer of interest. ‘I came to see if you maybe wanted to chat about your days with Wolf’ .”Yeah, well… I don’t know if anyone wants to know about those days,’ he said, non-committally. ‘I do, if you’ve got time.’ ‘Well I ain’t got time right now, I’m kind of busy. And it’s cold. This weather is just too cold for me.’ Willie Johnson, a man with time on his hands, was telling me in his own polite way that he wasn’t going to talk, ever. I could arrange another meeting when the weather was warmer and he’d be gone then, too. Knowing I’d bugged him enough, I headed for the door, with a sorry for having disturbed him. ‘Thanks for dropping by,’ he said, without getting up.

A few months later Michael Frank returned a call asking for an update on Johnson’s record. ‘You didn’t hear?’ he said, surprised. ‘Willie finally drank himself to death. The landlord came in and found him on the floor with a bottle in his hand.’ It had happened in February ’95, about 10 weeks after the abortive meeting. Frank had been one of the few outsiders to see Willie in the last year of his life, and had often talked with him about the reasons behind his parting from Wolf, and the consequent break-up of one of the America’s finest electric Blues outfits .’Willie knew why Wolf had to let him go, I think he knew it was his responsibility.’ ‘Why? ”Drank too much and argued too much.’

*****