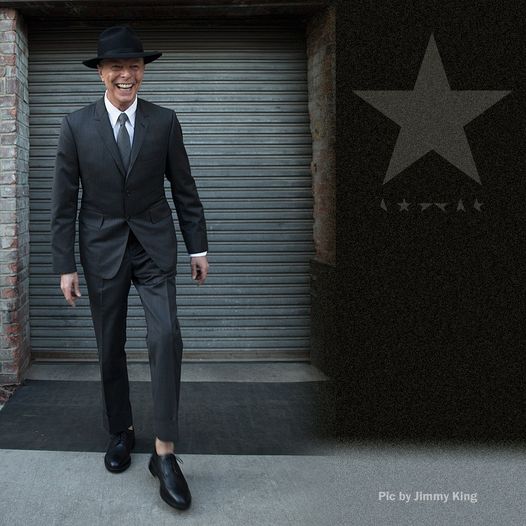

Lead photo is by Jimmy King, a press shot shared on January 7, 2016, with the caption: “”How is this man so happy?” Maybe because he knows his new album out tomorrow is already number one in the UK and it’s a bomb? “

I remember those days well; I’d just returned from watching two performances of Lazarus in NYC and chatted to Donny McCaslin on a BBC news programme the day before, where we both talked delightedly about the thrill of making and hearing Black Star. Now we’re approaching two potent dates: what would have been David Bowie’s 70th birthday, on January 8, and the anniversary of when the Starman left us, on January 10 (the news broke the day after).

The updated edition of Starman, published October 2016, contains most of my thoughts on his last, magnificent disappearing act. However, to mark these days, I thought I’d add a trilogy of pieces on Lazarus. I will add the successor stories over the next couple of days.

It was Julien Temple who first mentioned, in David’s mysterious layoff, of his long-treasured fantasy of a “Houdini disappearance”: the ultimate act of a career that was always a blend of modern high-art enigma, and old-school Hollywood showmanship. From the moment the Starman’s career took off, his vision always relied on a distinctive blend of long-term planning and short-term improvisation. The play Lazarus, inspiring, confusing, thrilling and visceral, would be the ultimate embodiment of this working method.

Lazarus, its main proponents tend to agree, was a meditation on mortality. But it wasn’t specifically about death, especially not at the beginning – which dates back a full decade. David had bought the rights to Walter Tevis’s novel of The Man Who Fell To Earth by 2005, when he gave an inscribed copy to his friend, theatrical producer Robert Fox. Inside it was written: “Robert, I’m not a human being at all. Thomas Jerome Newton. Shhh… David Bowie.”

Just a couple of years before, David had told MOJO how his long-term ambition had been to make musicals. Then in July 2013, within a couple of days of his private view of the V&A exhibition, David called Fox to a meeting at his London hotel. He explained he wanted to construct a sequel to The Man Who Fell To Earth. “It’s based around the character I played,” he told Fox. “And it’s called Lazarus.”

Only the economy with which he addressed the work suggested its importance: “He was always quite… elliptical,” says Fox. “He never went into huge detail but you knew if he brought something up it had importance for him. Specially around work. ” It was at that first meeting in London, Fox recalls, that David “asked, Who are the great young writers? And I said, Enda Walsh.”

Recently, on the BBC and elsewhere, there have been suggestions that David only knew his illness was terminal in the autumn of 2015. That’s consistent with what the Lazarus crew remember – but it’s worth stressing, neither they nor David addressed this issue directly. They got on with work, and David did the same.

In the event, David read through many writers’ scripts, then agreed that the Irish playwright’s explosive, thrilling style, full of confusion and dysfunction, was perfect. Enda, on holiday in New Mexico, got a call to meet Bowie and Fox in New York in September 2014. Thrown in the deep-end he was soon immersed in conversations all about “Newton. This man who can’t leave and who can’t die. And it stuck.” In essence, this work would played out in the alien’s own head: “It’s a journey into the internal, into mind.. into trying to wrestle something. What is that apartment? It’s not an apartment, it’s a head, a mind. Then the rules are out of the window… we’re passing narrative completely through this unsettled mind. And it becomes about the conversation a person is having with themselves.”

When I interviewed Enda, Michael C Hall, Henry Hey and Robert Fox, I was requested not to ask them when they “knew” David was ill. I didn’t resent the request – for one thing, there’s a crass element to that kind of question. When you know anyone who’s dying, at what point does it become reality, anyway? As we shall see, David was economical with what he told people; but right from their first drafts of the script around the end of 2014, Walsh knew he was dealing with some heavy, profound stuff: “Suddenly… it became a discussion about a man having this fight with himself about his own mortality. This wish to find rest. In a world where he’s an alien. So very quickly we were talking about it, working on it, writing it.. a lot of the big plays are about dying. And I thought fuck, we’re doing that. Right. OK.”

Talking to Enda, I felt I was being shallow at time, hardly asking about his other work – which must have been an influence on David, for his incandescent Disco Pigs unleashed Cillian Murphy on the world, and Cillian of course would eventually power Peaky Blinders, which we know became a near-obsession for David (it’s suggested that Tommy Shelby’s “Black Star” day, when he planned to rub out his rivals, inspired the title of David’s final album). Disco Pigs is itself exceptionally heavy stuff. I can’t help thinking of how Walsh’s genius for depicting the thrills, sadness and madness of life made him the perfect collaborator, and wonder how David felt as he investigated Walsh’s work.

Walsh is a visionary writer, his work shows. But it’s worth pointing out how many of the visionary elements were actually sketched out by David, in detail, in the earliest days of their collaboration: “He mapped it out for me. That we have Newton, this dead girl and this woman who over a short period has this mental breakdown and becomes this other woman, Mary Lou. And this man, Valentine, who just wants to fucking kill love!” Over the autumn of 2014, Lazarus was shaped by Bowie and Walsh together, with Bowie updating Fox via email, to share his enthusiasm. In the early days, the Ellie character was called Ellie Lazarus; that was changed, but the central concept remained: “Lazarus is of course the overall title for the situation the person is in – that transitional thing of being in purgatory and now not, a man trying to find clarity and rest.”