Johnson’s replacement, Hubert Sumlin, would become Wolf’s greatest collaborator. A young pup whom Burnett regarded as practically an adopted son, Sumlin had been hanging out in Memphis with James Cotton and Pat Hare before he got the call from Wolf . Nowadays Hubert is more or less retired, and has moved away from the noise and crime of Chicago up to a peaceful suburban street in Milwaukee. Hubert and Bee Sumlin’s house is brightly painted and looks as if it’s made of gingerbread, with little garden gnomes outside, and an interior filled with cuddly toys and lace. Hubert himself has the friendly, guileless demeanour of a teddy bear, and laces his stories with self-deprecating jokes and sneaky metaphors, all of which remind you of his eccentric, mercurial guitar playing. He greets you like an old friend, and after Bee has plied you with coffee and cakes takes you down to his inner sanctum, where he plays guitar and listens to records late into the night, accompanied only by Lucky, his laid-back and ludicrously fluffy cat. It’s years since he’s had a good talk about Wolf, and he enjoys telling the story, slapping you on the knee to emphasise the good points.

‘Like I told you, I was just a little bitty old boy coming up and I come by this old warped record in this old garbage pile, and I put this record on and it was so warped, really wooh waaah, I said oh shoot, and it sounded alright. I asked my daddy who it was, and he said, this is a guy died before you was born, and it was Charley Patton. Later on, Wolf told me that was how he started out too, as a little old boy listening to Charley Patton.

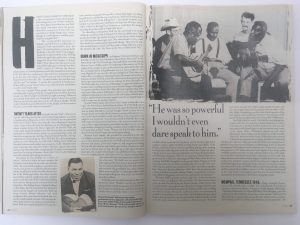

‘I played with James Cotton, he had this little band in West Memphis, Arkansas. Wolf was already established, and I was just this little old boy checking him out. Scared me to death, he did. Then one day I’m staying with Cotton at this old hotel and I get this call from Wolf. He said, Hubert, I’m putting this band down and I’m going to Chicago and forming me a new group, ’cause these guys, they think they’re too good, they don’t wanna play, and this and that. I said okay. Like that. I didn’t believe him. I really didn’t. And so Cotton said, hey man, you know he meant what he said? I said hey, I sure hope so. I would like to play with the guy.

‘Sure enough man, two weeks later, he calls up the hotel, tells me the train leaves at so and so time and you are going to be met by Otis Spann, Muddy Waters’ piano player. I said thank you. And that’s what happened. I packed my little suitcase, gets on the train and finally arrives at the big ol’ Illinois Station on 12th Street. Otis Spann met me, man, I got to see all these big lights, and I got scared and everything so we went on straight back to Leonard Chess’s daddy’s apartment building. Wolf had his own apartment there, he got me an apartment there and had done got my union card and everything. So the second day, me and Wolf we done had lunch, and he starts to telling me how this worked, how that worked, and we’re sitting around the apartment, going over the numbers and hey, I got to like that old man. I was kind of scared of him at first, he was so big and huge, you know what I’m talking about, but that didn’t last long – he was just like a little baby if anybody knowed him, man.’

Wolf ran his band like a machine, dictating what clothes they should wear, paying their union dues, finding them accommodation, and, in Sumlin’s case organising guitar lessons: ‘I had just started playing with him, man, and I wasn’t seasoned good enough, and Wolf said, hey Hubert, tomorrow I want you to go with me, I’m gonna show you something I think you are going to like. Sure enough, he took me downtown to the Chicago Music Conservatory of music, this is where Wolf took lessons, and then he paid for two years’ lessons for me. It was some opera guitar player, name was Gowalski, he was playing symphonies over in Europe and now he’s teaching me scales and stuff! ‘Cept I only took six months lessons ’cause the guy dropped dead right in front of me of a heart attack. But hey, with what he taught me and what I knew, I made out.’ Although Wolf had a reputation in Chicago for whupping any musicians who didn’t toe his line, most musicians who worked with him considered him the best bandleader in the city. Jimmy Rogers, Muddy Waters’ long-term guitarist, remembers: ‘Really Wolf was better managing a bunch of people than Muddy or anybody else. Muddy would go along with the Chess company, Wolf would speak up for himself – and when you speak up for yourself you’re automatically gonna speak up for the band.’ As Billy Boy Arnold, a regular on the Chicago club circuit puts it: ‘The difference with Wolf was, if you played in Wolfs band and got fired or quit you could draw unemployment compensation. If you walked up to Muddy and said something like unemployment compensation theyd think you were crazy, what the hells that? Wolf would be sitting in the corner with his spectacles on in intermission, studying his book, he went to night school, he took music lessons, he was always trying to advance. He was a guy stayed on top of things. When you went to see Wolf he would be on that stage kicking ass all night long. I used to play in clubs with Muddy in the late Fifties, and Muddy used to let Cotton run his show – he would only come on for the last few numbers. Muddy was a great artist, but he became less of a draw in the Chicago clubs than Wolf, until the white audiences came along and rescued him.’

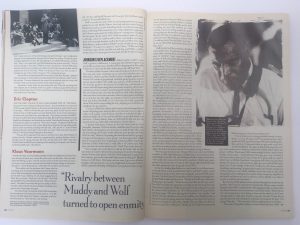

As the two leading band leaders in a city known for cut-throat musical competition, it was inevitable that Waters’ and Wolf’s rivalry would develop into open enmity. Waters had originally welcomed Wolf to the city but by the mid Fifties the King Of Chicago Blues was becoming increasingly paranoid that Wolf would steal his crown. ‘Muddy and Wolf , they really had a feud going,’ says Sumlin. ‘Those two were just like the McCoys, man!’ The rivalry extended to arguments over who got the best songs from the Chess house songwriter, Willie Dixon, and constant attempts to poach the others’ best musicians. In 1956 Waters pulled off a particularly satisfying coup: ‘We were playing the Zanzibar,’ says Sumlin, ‘ and Muddy sent his chauffeur over in his Cadillac, the chauffeur had on diamonds and everything, and I am looking at this big roll of money, I ain’t saw so much in all my days. Muddy done sent him over there to bribe me, man! He’s telling me, Muddy say he’ll triple the money that Wolf paying you, what do you want to do? ‘Course when you’re young you think money’s everything, so I say alright, and I’m wondering how am I gonna tell Wolf. I got this money, 400 and something dollars, and it is 10 minutes before we get ready to go back on the bandstand. The place is full of folk, jammed, so I goes in the bathroom to count my money and to think about what I am going to tell him. Shoot man, Wolf comes straight in there, and he done change colours, man – he got blacker! This guy got a ton of colour I ain’t never seen a man turn. I say, oh shit, he is gonna kill me, man! I didn’t have to tell him ’bout how I was going with Mud, the guy knew already. He says to me, “get out of my sight, get your stuff off the bandstand now”. In the middle of the show! I takes my shit down, scared, trembling, just knowing I’m gonna get bopped any minute, and get out of there quick as I can. Mud’s chauffeur must have had an idea what was going on, he’s waiting on me outside, helps me put my amplifier in the trunk and drives me over to Sylvio’s, where Muddy is at. Man, I cried a-a-a-all the way over there.’

From the moment he’d joined the Waters camp, Sumlin started to miss Wolf’s comparatively well-organised outfit, not least when the Waters band set out on an arduous tour of the South: ‘Mud told me we were leaving town, we’re fixing to leave and he asked me did I have enough clothes, I said, sure. I had me one suit. He said “is that all you got, just that one suit? You know we gonna be away about 40 days?” I’m going, what the… this man ain’t told me nothing about no 40 days, so I hit the road with them. Man, that 40 days like to kill me. Some of them jobs was a thousand miles apart man, nothing under 500 miles, 20 days out of the 40 didn’t nobody get a chance to take a bath, ’cause by the time we arrive in the next town it’s time to play. Man, we did so much driving, I got the haemorrhoids so bad I couldn’t sit down! They brought me feather pillows that I had to sit on! We drove about 14 hundred miles back to Chicago, and the moment I got back in town I called Wolf, I said I got the haemorrhoids, this guy done work me 40 days and 40 nights, I said I am quitting Mud and I wanna go back with you. He said, you say you’re comin’ back? I said, I’ll be there in three minutes, man. And that’s how I went back to Wolf.’

*****

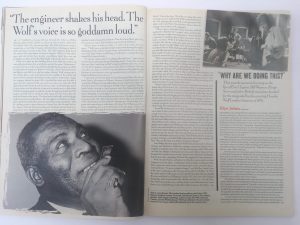

It’s a quiet mid-week night at Buddy Guy’s club on South Wabash, Chicago, and only a few punters are sitting at the bar as the quiet-spoken guitarist orders two Heinekens on the rocks. Guy, looking slick in a white jacket, with a long process hairdo, looks impossibly young to have played in practically every one of the city’s legendary clubs, with practically every one of the city’s major acts. Now Chicago’s best-known Bluesman, Guy longs for the days when he was a new boy in town, and the likes of Wolf were playing five nights a week: ‘It’s strange, you know, I didn’t come to this city to be anything, I came here to work in the day and watch people like Wolf at night. That’s all I wanted to do, sit there and watch while I sat over one Coke for six hours. I could never explain really what seeing Wolf was like. I had his records, 78s, then I walked into a club and find this big man crawling around on his knees, dragging his tail and howling like a Wolf! Then you hold a conversation with him, and this guy’s not faking this tone of voice, it’s natural, and I’m saying, oh my God – who am I ? ‘Cause I know who he was, and who am I to be talking to him? It’s like I’m in heaven and I don’t even know it. Chicago was a place nobody slept, it was a round the clock thing, the city buses was running all night and there was a thousand night clubs here, every one of them was packed. We had the stockyard going 24 hours a day, the steel mill running 24 hours a day, and I actually lived in Chicago for about five years and lost track of which was the weekend. I know we can’t bring those days back, but I would be a happy man if we could only give those guys credit for what they done, for originating the music you’re hearing now.’

Buddy Guy’s arrival in Chicago signalled the ascendance of a younger group of slicker soul-oriented Bluesmen including Magic Sam, Otis Rush, and Guy himself, who threatened to supplant Wolf and Waters much as they had replaced their acoustic forebears a decade before. But rather than surrender to these young turks, Wolf incorporated them into his sound, using the likes of Buddy Guy or Freddie King to augment his recording group. The result was a string of records, many of them from the prolific songwriting pen of Willie Dixon, which combined Wolf’s brutal delivery with innovative songs such as Wang Dang Doodle, Back Door Man, Spoonful or Killing Floor. These songs bore scant resemblance to much of the ritualistic 12 bars that pass for Blues today, for their imagery and arrangements would anticipitate – and arguably surpass – much of the late Sixties Rock of Cream or Led Zeppelin. Wolf’s band conjured up a kind of voodoo modernism, coupling Wolf’s supernatural vocal delivery with subversively memorable backings made up of loping, off-beat rhythms and perfectly judged guitar hooks. And you could dance to them, too. Sumlin recalls that most of these classic songs resulted from intense experimentation in Wolf’s basement, and some very gruelling studio sessions: ‘We wanted to take this thing somewhere new, but we didn’t wanna stray too far from our roots, you know what I mean? But mostly we was trying to get as low-down and dirty as we could. We’d sit there and talk about the song, is this going to be somebody telling a story, who did this, who did that, did somebody kill somebody? You gotta think about what you saying and it better fit. And you also got to have your instrument together and your voice together, and it’s gotta be where somebody can feel it, where there is going to be some soul there, this is what it is all about. If you can get that together in two hours, or one hour you’re alright – you’s a genius I think!’

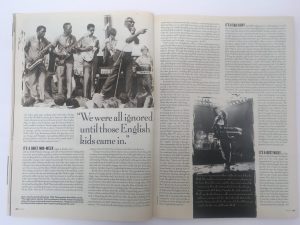

Wolf’s classic run of singles from 1956 to 1964 would remain unsurpassed in the Blues canon, scoring him hits with his black audience well into the Sixties, and, gradually percolating through a growing audience for R&B in Europe. Although bands such as the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds are historically credited with introducing Wolf’s music to a white audience, Wolf’s first English success derived from the Stones’ contemporaries, rather than their fans. From the very beginning of the Sixties, American R&B releases were being avidly consumed by the pre-Who mods and art school beatniks, including the future Rolling Stones. As influential champions such as Mike Raven, from the Radio 390 pirate station, and Guy Stevens, DJ at the Scene in London, started spinning black American R&B material, other promoters, including Rik Gunnell of the Flamingo, started booking Blues acts into UK Clubs. By 1962, when the ultra-cool Pye R&B label started distributing Chess material in the UK, Wolf’s records were about the hippest thing on UK dancefloors. In a heart-warming demonstration of British good taste which would be repeated later with the likes of Jimi Hendrix or Nirvana, Wolf’s first crossover hit was scored in the British charts, when the Pye re-release of Smokestack Lightning reached 42 in June 1964. A bemused Wolf embarked on his second European tour shortly afterwards and according to Sumlin, ‘as far as the old man was concerned, he thought he’d died and gone to heaven. Those people over there, they treated us like kings… in fact we got kinda spoilt as far as going back home.’ Crossover success in Wolf’s homeland proved more elusive, despite Chess’s attempts to package their artists for the ‘Folk Blues’ audience. The real breakthrough would come via The Rolling Stones, who covered the Red Rooster in October 64, and engineered Wolf’s appearance on the Shindig ABC-TV show in May 1965.

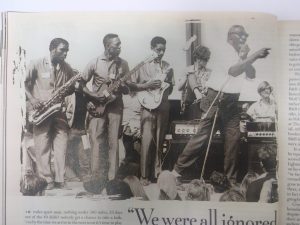

The news that Wolf had appeared on national TV sent seismic ripples through Chicago’s Blues community, who for the first time became aware of the English bands covering their material. A few musicians were cynical about their motives. Not Wolf. ‘It was the light at the end of the tunnel,’ says Buddy Guy. ‘There was a boundary line which no one thought could be crossed, and the Rolling Stones broke it by getting Wolf on that show. That was something we would never even have thought of, the hairs were just standing on my head. We talked about it later, he said about how the man next door don’t know who I am and here’s some British kids from thousands of miles away, we laughed about it, and I know he was proud of what happened. ‘Cause as far as the record companies or the news media or anything, we were all ignored until those English kids came in.’

It’s a sad irony that Wolf’s adoption by a white audience would become a major factor in the irrevocable decline of his recorded output. First of all Paul Butterfield poached Wolf’s rhythm section, Sam Lay and Jerome Arnold, winning himself Brownie points for fronting a racially integrated band, but also earning Wolf’s undying resentment for breaking up one of his finest line-ups. Then Marshall Chess, aiming to cash in on West Coast Psychedelic Blues, oversaw an ill-judged attempt to update Wolf’s sound. ‘We get down there to the studio,’ says Sumlin, ‘and these guys had wah wahs and everything else on there, waiting on us. Wolf didn’t like it, so he went home and got into bed for three days, until these dudes got through with the psychedelic stuff. Three days they tried to get Wolf back down, finally they got him to put his voice on – he said I’ll sing the number, just cut the music off, I don’t want to hear that goddamn Wah Wah. That man was dedicated to his stuff, but they wouldn’t take no notice of him.’ The resulting album, New And Unimproved, was destined to be forever known by Wolf’s altogether more succinct title. He called it The Birdshit Album. 1970’s London Sessions was a slightly more successful attempt to update the Wolf formula, an experience that was successful on a personal, if not a musical level . ‘He genuinely enjoyed all that,’ says Eddie Shaw, who played sax in Wolf’s band and later became his personal manager. ‘He didn’t feel it was strange playing with these English kids, ’cause he was a nice person, and enjoyed trying to teach them what the Blues was all about. About ’74 when The Stones came to town, Wolf had Bill Wyman as a guest at his home, they spent a lot of time together, and that was because Wolf really liked them. He was just glad he could help put them on the right track.’ Now in his sixties, Wolf believed he had to pass on his music, as Patton had passed it on to him, and continued to attempt to push Hubert Sumlin into a frontman role, with little success. ‘He was getting old, and he was about as happy as you could be,’ says Buddy Guy, ‘He’d joke, say I know I’m getting on and I can’t get around like I used to do, but you boys had better look out, ’cause the old man gonna drag his tail tonight. I don’t think he was an angry man, he accepted life – when you’re religious you accept what life has given you whether it’s bad or good, and he saw some things I don’t think he ever thought he would see, like going to Europe, and a lot of other places he never dreamed of.’

****

It’s a busy night at Club Blues on the Chicago Northside, and once the tour guide has negotiated the group discount for his excited charges, they rush quickly out of their air-conditioned bus into the sweaty club, careful lest they should catch a chill on the windy snow-filled street. The club is now a compulsory spot on the tourist itinerary, promising a vicarious thrill for the dentists and attorneys attending city conventions, who regard their trip to the safe white area as an erotically dangerous walk on the wild side. Whether or not they realise it, they’re more likely to witness a historic moment than they probably deserve, for Club Blues hosts dozens of survivors from the glory days who still set out to prove they’re more than just museum pieces. But their ranks are thinning. Wolf’s boys – Sam Lay, Henry Gray, Detroit Junior, Ray Scott – still play regularly around the city, but Little Smokey Smothers has recently undergone open heart surgery, and SP Leary, who played with Wolf on and off for nearly 15 years, has been forced to give up drumming after a stroke. ‘But I ain’t given up on life,’ he objects. ‘I’m stronger than cancer, I’m stronger than the stroke… but God’s stronger than everybody. When your time is up, you gone. Might as well get on and let the good times roll while you can. You go and tell ’em all he said that before he croaked.’

The main attraction at Club Blues tonight is Eddie Shaw, who played along with SP on Wolf’s last album. Eddie remembers Wolf’s last years were characterised by similar sentiments to those of his drummer. ‘The old man would never give up. He knew what was going on, but he wasn’t giving up. I used to run my own club, the New 1815 on the West Side, and one night about 1973 I get this phone call, it’s Wolf and he’s saying “I think you need help at your club.” I said what do you mean, I don’t need no help. So he goes, “I tell you what I’m gonna do. I’m gonna come over to your club every weekend and play.” I go, are you asking me or telling me, and he says: ‘I’m telling you.” So that’s where he played every weekend. Sometimes we’d go out and play in the week, whatever cities we could go to where they had the dialysis machine – his kidneys were starting to give out after he had an auto accident. But the man was still taking music lessons, we would still meet twice a week and talk about what was happening in the music business and everything else. He wasn’t just gonna sit and sing these old Blues songs about the Thirties. That’s why we were working on new material, ’cause the old man was up with what was happening in the world.’

Wolf’s last album, Back Door Wolf, was a fitting reflection of the grand old man’s dotage. Although the arrangements and some of the songs were a far cry from Wolf’s glory days, his voice was still magnificently untamed, as he howled his defiance in songs such as Coon On The Moon, where he summoned up white America’s darkest nightmare: ‘you know they call us coons, say we don’t know no sense, you gonna wake up one morning, and a coon’ll be president.’ Defying his failing kidneys, his failing legs, and a changing world, the Wolf roared every weekend at Shaw’s club’s until just a few weeks before his kidneys finally gave out, in January 1976. As predictable as it was, for all of his band Wolf’s passing was a profound shock. They simply couldn’t imagine a world without him.

‘Course, I should have known,’ says Sumlin. ‘Things don’t last always, none of us will be here all days. But I never thought Wolf would have been dead. I thought he would have lived longer than me, I don’t know why, I just figured I would have gone first. But things went the other way, so hey, I am here, and I guess we all must be here for something. But somebody had to love this music at the beginning, and in my time I found out that this is true music. This music tells a story, about the people that lived this life and is still living it. And so this music will always be here. So I’m telling you, it ain’t sad, ’cause this music will always be here.’