A repost from my old Website, original posted March 18, 2009. I report this in thanks for the beautiful times I spent with Ron, and also in tribute to the recently-departed Scott Richardson, always an insightful and generous interviewee, plus Robert Matheu.

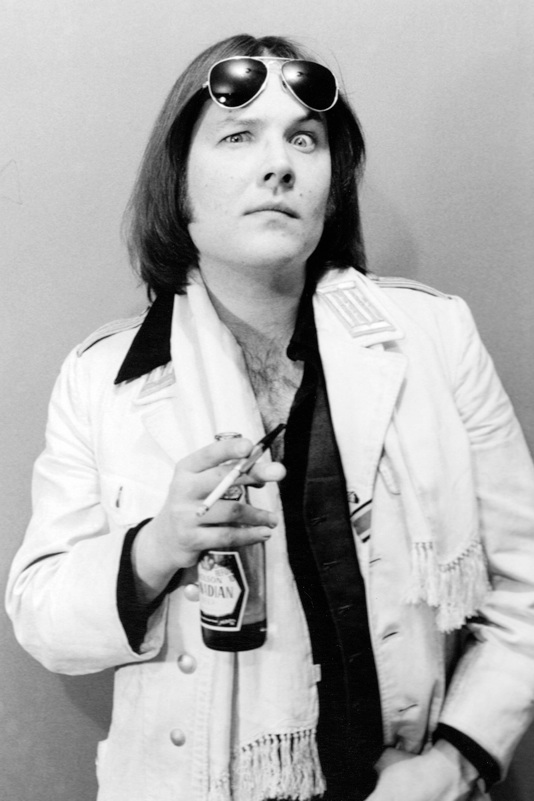

Photo courtesy Robert Matheu www.robertmatheu.com

Simpson the cat is ailing, advanced in years. Ron Asheton breaks off from his stories of heroin, macrobiotic rice and aluminium afros to attend to him gently, pouring a saucer of milk and checking on his medication. This is the man who similarly ministered to his fellow Stooges, cooking for them in the house in which we sit, working in the Pigments Of The Imagination head-shop to subsidise their meagre earnings, removing lit cigarettes when they’d nodded out. These days – 1995 – he simply ministers to their legend. Occasionally he’ll drop in on brother Scott, or call ex-guitarist Bill Cheatham, or drive down to the Big Ten store on Packard for his Canadian cigarettes, and remember how the Stooges would walk over from their Fun House to pick up beers. The stories he tells are exhilarating, how his band challenged all comers and won. And they are sad, for the band lost, too. Dave Alexander, his childhood friend, “a personality just as fascinating as Iggy,” dead. Zeke Zettner, a sweet boy, the Stooges’ roadie-turned bassist, dead too, along with his brother Miles.

Together, we struggle for a meaning in this story, which is fractured, for his boyhood friend, Iggy, is gone and Ron grieves for him too, that they can’t have “even just a casual relationship.” Just as the Stooges struggled for recognition by a hostile world, he struggles for recognition by his former singer, just a sign that all of this craziness makes sense. I leave that morning with regret, just after Ann Asheton gets up early to head for a collectors’ fair, quizzing Ron to make sure he’ll look after the cats. It seems a strange twist in a twisted tale; of course, there were plenty more twists to come.

The story of the Stooges is celebrated, legendary even, both for the band’s inspirational music, and the uniquely chaotic circumstances which spawned it. Ron Asheton epitomised both. Dead of a suspected heart attack in his Ann Arbor, Michigan home at the age of 60, Ron had finally achieved widespread recognition, playing to huge crowds from South America to Europe, treasured once more by his childhood friend and celebrated by cognoscenti as a founding father of punk and alternative rock. As one friend, Michael Tipton, puts it, “the great thing is he finally tasted some respect. But it should have happened a hell of a long time ago, and there should have been a hell of a lot more of it.”

Although bandmate Iggy Pop’s upbringing in an Ypsilanti trailer park is celebrated, it was Ronald Asheton Junior who lived through a more traumatic childhood. The Ashetons were a happy, tight-knit family who lived in Maryland; Ron, born in July 1948, learned to play accordion from the age of five, assisted by his great aunt Ruthie, an occasional vaudeville performer. Then on December 31, 1963, Ron’s father – Ronald F. Asheton, an ex-Marine Corps aviator – died. Ann Asheton, a resourceful mother, moved the family from Davenport Island to a new life in Ann Arbor, single-handedly supporting them with a job in the Ramada Inn.

Ron, younger brother Scott and sister Kathy were all engaging characters, sharing a dry humour which would become a defining aspect of the Stooges’ mentality. Of all of them, Ron’s humour was the driest, a trait which would become key to his survival. That humour never stretched to cynicism, though, for Ron was an enthusiast, in thrall to the dream of rock’n’roll. It was this dream that inspired him to drop out of Ann Arbor High along with friend Dave Alexander in 1965 to check out Swinging London first-hand. Ron and Dave expected to see The Beatles walking down Carnaby Street, but had to settle for the alternative of seeing The Who play at the Marquee. It was a happy substitute, because if anyone influenced Ron’s unique guitar style, it was Pete Townshend. For many years Ron’s most treasured possession was a shard of Rickenbacker, sacrificed that fateful night.

It was soon after returning from England (Ann Asheton had to wire him the money for the flight home) that Ron briefly teamed up with his high school acquaintance Jim Osterberg in Ann Arbor blues band The Prime Movers. For a few rehearsals they made up a rhythm section with Ron on bass, and Jim – whom the Prime Movers nicknamed Ignatius, or Iggy for short – on drums. Sadly, the Movers’ leadership duo, Mike and Dan Erlewine, decided Ron was hampering their purist blues recreations, and he was demoted to roadie before finding a new job in Ann Arbor’s snotty garage band The Chosen Few, alongside singer Scott Richardson and, briefly, guitarist James Williamson. For years thereafter, Ron would reminisce proudly of how he had christened Detroit’s legendary Grande Ballroom as a rock music venue, when he played the bassline which introduced the Chosen Few’s cover of the Stones’ Everybody Needs Somebody, for their support slot to The MC5 in October 1966. Later that year, Chosen Few manager Ron Richardson (who also briefly managed The Stooges) started up his rickety Plymouth Washer Service Van and drove the band to New York City, where they scored a singles contract with MGM; the deal fell apart when Ron belatedly realised all his charges were under age, and the band’s parents, bar Ann Asheton and the Richardsons, refused to sign on the dotted line.

It was some time in the next Spring that Jim Osterberg abandoned his drumming ambitions and teamed up with Ron. Their initial intentions were vague – there were plans that Scotty might sing, that Iggy might play drums or Farfisa organ, and for their first appearance at an invitation-only party, Ron played bass – but over months spent living together at various band houses around Ann Arbor, the band slowly evolved their own sound. It was slow work, like Henry Moore chipping away at an immense slab of granite, but the results were just as imposing. It was Ron who named the group – the Three Stooges, along with John F Kennedy and Erwin Rommel were his heroes. And it was Ron who, more than anyone, carved out their sound. In the earliest days, the Stooges’ music was completely freeform: screams, noises and found sounds from a vacuum cleaner or a blender overlaid with wah wah guitar and Bo Diddley drums, but bit by bit the Stooges discovered how to do more with less.

These days, of course, Ron is regarded as a progenitor of punk guitar, but that label belies the subtlety of his playing. Although he was a master of bludgeoning riffs, as on 1970 or Loose, there are all sorts of clipped voicings or droning notes which characterise his playing: songs like Now I Wanna Be Your Dog, 1969, or No Fun are precise, almost stately – indeed, as Iggy once told this writer, “Ron has an elegance as an instrumentalist and as a writer that I lack”; he also pointed out how Ron had “beautiful”, pianist’s fingers. Without a doubt, Iggy was the one who shaped this music, gave it lyrics, direction and a persona. But Ron created it. As Scott Richardson points out, “ There’s only a few people in his category: Pete Townshend, Ray Manzarek and Ronnie, instrumentalists who created their bands.” He was as influential as those two peers. One generation of musicians – The Pistols, Damned and Ramones – adopted his bludgeoning style, another – including J Mascis, Thurston Moore, the Pixies and Kurt Cobain – incorporated those subtler, droning effects, too.

As Ron described it in later years, those early “Stooges times” were perfect, as if the whole band was living through a dream: “It was magical, a time when I could just sit down and come up with the shit.” Even the early audience hostility and the derision of fellow musicians couldn’t dent their collective self-belief. That self-belief endured through two wonderful albums, The Stooges and Fun House, but it was eventually destroyed by drugs. In the early days, pot and LSD had inspired their music, but by the time they came to record Fun House, Iggy was dropping acid every day, then he and drummer Scott progressed to cocaine and heroin. Once bassist Dave Alexander was sacked after an alcohol-related lapse at the Goose Lake Festival in August 1970, the Stooges fell apart with terrifying speed. Worst of all for Ron, the one member of the group who had not succumbed to hard drugs, he was sundered from his best friend Iggy and his brother Scott. The singer, drummer and new guitarist James Williamson moved to a high rise, University Tower, that was nearer to the band’s drugs suppliers. Ron and bassist Jimmy Recca remained in the band headquarters, the fabled Fun House, subsisting on vegetables they grew in the garden. In the end, the building was condemned.

Dropped by Elektra, the band split. Worse was to follow. After a chance encounter with David Bowie in September 1971, Iggy relaunched his career. Ron was deemed surplus to requirements; in his place, Iggy chose James Williamson. When Ron heard the news at a party for Scott Richardson’s new band, the SRC, he walked home, crying all the way. Such humiliations, dreams ripped away from us, can define a life. The fact that James and Iggy, after checking out musicians in London, finally called in Ron and Scott to make up their rhythm section was one more humiliation – “schmuck city for my brother and me.” But it was a humiliation Ron rose above, for he was a brilliant bass guitarist; “a master,” as Scott Richardson puts it, just as he had been in the Chosen Few. When that line-up of the Stooges crashed and burned after recording the incandescent Raw Power, it was Ron whose humour sustained those around him in a disastrous last tour, a catalogue of disasters that he memorably described as “beating a dead horse… until it was dust.” Fought to a standstill, The Stooges split once more, and while Ron continued with his own bands, The New Order and Destroy All Monsters, Iggy was taken up by David Bowie – and when he decided to collaborate with ex-Stooges it would be James Williamson, or Scott Asheton, who got the call. And that, it seemed when I met Ron in 1995, was that.

Having met Iggy several times and finding him uniquely intelligent and entertaining, perhaps it was no surprise to find Ron his equal. Iggy’s life story was picaresque, Ron’s was more so, especially when it was related to you in the house where he’d lived since a child, with his mom asleep upstairs, while Ron ministered to his cats, generous with tea, toast and grass – all of which he imbibed with discrimination – or proudly bringing out his collection of firearms, which if memory serves included both Chinese and Czech variants of the AK47, a Luger Parabellum, Walther P38, Glock 9mm, an Uzi and a Tec 9 machine pistol. He explained the engineering legacy of each weapon with erudition and freewheeling humour. The same applied to his knowledge of Bob Hope, The Bismarck, horror movies (a field in which he was lately working) and UFOs. He was hurt by the humiliations he’d endured, but not bitter. Indeed, at one point in the litany of Stooges disasters, I was overcome by an extended laughing fit. It was supreme bad taste, finding their travails comedic, but Ron was forgiving – “no go ahead, laugh, it’s OK, it was funny.” When we discussed his fixation with the Third Reich – which he essentially justified with the proposition that Hitler was the first modern master of marketing and stagecraft – we went into fine detail and I, as a Polak with a father who escaped from and a second uncle who was murdered by the Nazis, should in theory have been offended. But I agreed with his contention that the Germans did have the best uniforms and hardware. Unlike, say, Eric Clapton, who dabbled with similarly unpalatable politics, Ron was a kind person – one who cared for others, a man whose troubles had revealed a genuine nobility and fortitude.

So far, so extraordinary. Yet over the following years Ron’s devotion to the cause of the Stooges was repaid when he was called in to contribute music to Velvet Goldmine, Todd Haynes’ movie inspired by Tony Zanetta’s Bowie biography. That project turned into a tour with J Mascis and Mike Watt which drew indie kids to venues across the US. Iggy Pop took note, and a one-off contribution by Scott and Ron to Iggy’s Skull Ring album eventually turned into a fully-fledged Stooges reunion – a reunion that, despite all precedents, was truly magical. Many who’d seen The Stooges the first time around, including photographer Robert Matheu and Fun House producer Don Gallucci, whom I accompanied to the band’s inspiring recreation of that album at the Hammersmith Apollo, proclaimed them as, quite simply, better than the youthful version of the band they’d seen over three decades before. Although their reunion album was patchy, their best songs, including Idea Of Fun and their cover of Junior Kimbrough’s You Better Run, featured scything guitar playing that was equal to Ron’s magnificent work on Fun House.

Such fairytale endings are rare, and there is an almost unbearable poignancy to Ron’s comments on that show when I spoke to him a few weeks later. He was back in that dream that he’d had as a 20 year old, overwhelmed by its perfection. Fully aware of the irony of this turnaround, he looked on with raised eyebrow as kids mobbed the band, invading the stage, genuflecting before him (or even, on occasion, mooning him). Always the mother hen of the Stooges, Ron told me how he worried about the other band members, “because I don’t want to wake up from this dream.” He’d warn Mike and Scott to drive carefully, “and I tell Jim all the time, When you’re swimming, look out for rip tides and sharks.” It was a different kind of rip tide that claimed Ron, in that family home where the Stooges had once rehearsed. He had been out of touch for several days – something his friends were used to – and his band-mates had been calling him to discuss getting together to write new material. It’s sad we will never hear it. And now Ron, like Simpson, Dave, Zeke, Billy Cheatham and Ann Asheton is another memory. But at least he didn’t wake up from that dream.

Thanks to MOJO magazine for permission to reprint this feature from the March 2009 issue.

Wednesday, 18 March 2009

Leave a Comment